The Link Between Health & Behaviour

As a clinical animal behaviourist, I am trained to read between the lines when it comes to health and behaviour. Why is this a necessity as part of my job? Should I not just be focused on training dogs to behave well? I wish it were that simple!

An ever-increasing amount of research on canine behaviour and welfare links behavioural changes to their health. This should not be surprising, as the majority of us humans have experienced a change in our own behaviour when our health is compromised. Perhaps we are less tolerant of things when in pain, maybe we snap at our family members or spouses when we ache or we may struggle to focus on a task.

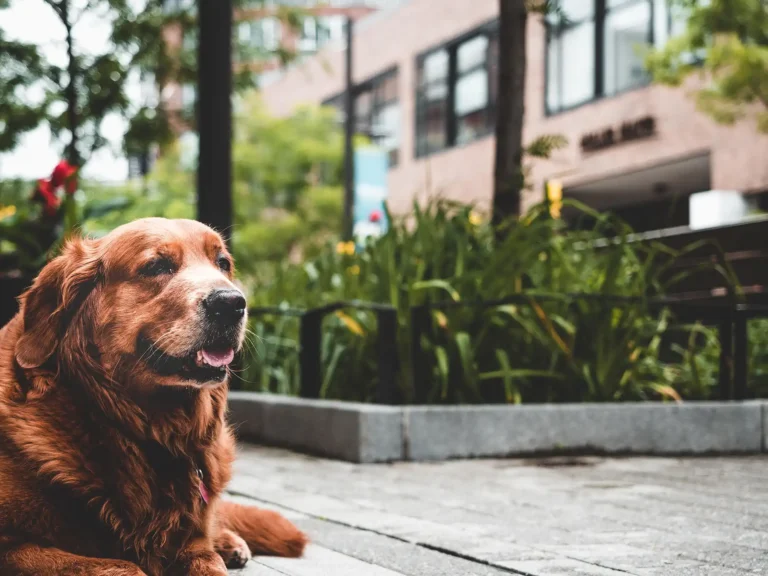

We can hide symptoms of pain and illness well. You may be talking to a friend without knowing they have back ache, you may be able to still go to the gym despite having a tooth ache. The enjoyment of an activity or the necessity to access resources that enable us to continue to live our lives can overshadow the punishing feeling of pain and disease. This is not uncommon with dogs, where they soon forget how sore they are when there is a ball or squirrel to chase.

All too often subtle signs of pain and disease (illness) are overlooked in dogs. It is adaptive to hide pain and disease-weak animals are more easily picked off by predators.Hiding weakness increases the chance of survival. Our domestic dogs retain these primitive needs and associated behaviours, despite living much easier lives than wild and free ranging canids.

Health issues are sadly rife in dogs. An ever-decreasing gene pool has resulted in breed-specific diseases which cross breeds are also not immune from.Additional factors such as neutering, diet, exercise and the home environment. It is thought that as many as 200,000 of dogs in the UK annually are diagnosed with Osteo Arthritis and one study found that 75% of cases presented to a clinic for aggression suffered from muscular skeletal pain (Barceloset al.,2015). Pain has also been linked to sound sensitivity/noise phobia in dogs (Fagundes,et al.,2018). We commonly see and onset of sound sensitivity in adult dogs-which makes one wonder, why now? (Assuming that no negative event has taken place). It is thought that the startle response causes pain, which leads to an association (sudden sound hurt me). Aggression has been linked to pain in numerous studies. One study (Mills et al.,2020) estimated that one third of behaviour cases were experiencing pain but speculated that this figure could be alarmingly as high as 80%.

A wealth of research is now linking behavioural health to the digestive system. This should be of little surprise when 90% of serotonin is produced in the gut. Serotonin is often considered to be the ‘feel good’ chemical of the brain, if the environment its produced in is compromised-how does this affect behaviour? Well, low levels of serotonin have been correlated to increased aggression in dogs (Cakiroğluet al.,2007). One study found that the microbiome in the gut of aggressive and phobic dogs differed to those without behaviour problems, revealing the potential for probiotics to assist in behaviour change (Mondoetal.,2020).

Have you ever had insect bites such as fleas or mosquitos? Can you recall feeling stressed from constant itching? Well, you may now not be surprised to learn that skin issues are often linked to behaviour problems in dogs too. Atopic dermatitis has been linked to behaviours associated with stress such as mouthing, chewing, hyperactivity, reduced trainability and excitability. (Harveyet al.,2019)

Interestingly, the vast majority of my behaviour cases show symptoms of gastro-intestinal disease. It’s sometimes hard to know what comes first, the behaviour problem or the gut issue-as stress can affect the gut. Indeed, stress can affect the quality of life and lifespan of dogs (Dreschel 2010) so we need todo what we can to protect them from health and behaviour problems.

What can we do? Fulfilling their species-specific needs provides a foundation for wellbeing, and the less stressed our dogs are the more likely they can fight disease or cope with pain.

Provide your dog with activities to do such as foraging, chewing and predominantly low intensity exercise. Ensure they get adequate and quality rest and sleep (12-16 hours a day)and as a social species, they should not be left on their own too often. Manage how often they encounter things they find difficult, reducing exposure to stressors as often as you can and allow plenty of time for recovery.

Supplements, such as those by Blue Pet Company, can support dental, skin and joint health and are a worthy addition to your dog’s life when fed along side a quality diet. I supplement all of my dog’s diets to optimise their health. If you are ever concerned that your dog is unwell or in pain, take them to your veterinarian.

If you are concerned their behaviour is related to their health or that their health has shaped their behaviour-book in with a clinical animal behaviourist. Refer to the APBC and ABTC register for more information on practitioners near you, although many now work online too.

Barcelos, A-M., Mills, David & Zulch, H., 2015. Short communication: Clinicalindicators of occult musculoskeletal pain in aggressive dogs.VeterinaryRecord, 176(18), p.465.

Cakiroğlu D, Meral Y, Sancak AA, Cifti G. Relationship between the serum concentrations of serotonin and lipids and aggression in dogs. Vet Rec. 2007Jul 14;161(2):59-61. doi: 10.1136/vr.161.2.59. PMID: 17630419.

Dreschel, N.A., 2010. The effects of fear and anxiety on health and lifespan in pet dogs.Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 125(3), pp.157–162.

Fagundes, A.L.L. et al., 2018. Noise Sensitivities in Dogs: An Exploration ofSigns in Dogs with and without Musculoskeletal Pain Using Qualitative ContentAnalysis.Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 5, p.17.

Harvey ND, Craigon PJ, Shaw SC, Blott SC, England GCW. BehaviouralDifferences in Dogs with Atopic Dermatitis Suggest Stress Could Be aSignificant Problem Associated with Chronic Pruritus.Animals (Basel).2019;9(10):813. Published 2019 Oct 16. doi: 10.3390/ani9100813

Mondo, E., Barone, M., Soverini, M., D’Amico, F., Cocchi, M., Petrulli, C.,Mattioli, M., Marliani, G., Candela, M. and Accorsi, P.A., 2020. Gut microbiomestructure and adrenocortical activity in dogs with aggressive and phobicbehavioral disorders. Heliyon, 6(1), p.e03311.

Pilla, R. and Suchodolski, J.S., 2021. The Gut Microbiome of Dogs and Cats, and the Influence of Diet. Veterinary Clinics: Small Animal Practice, 51(3),pp.605-621.